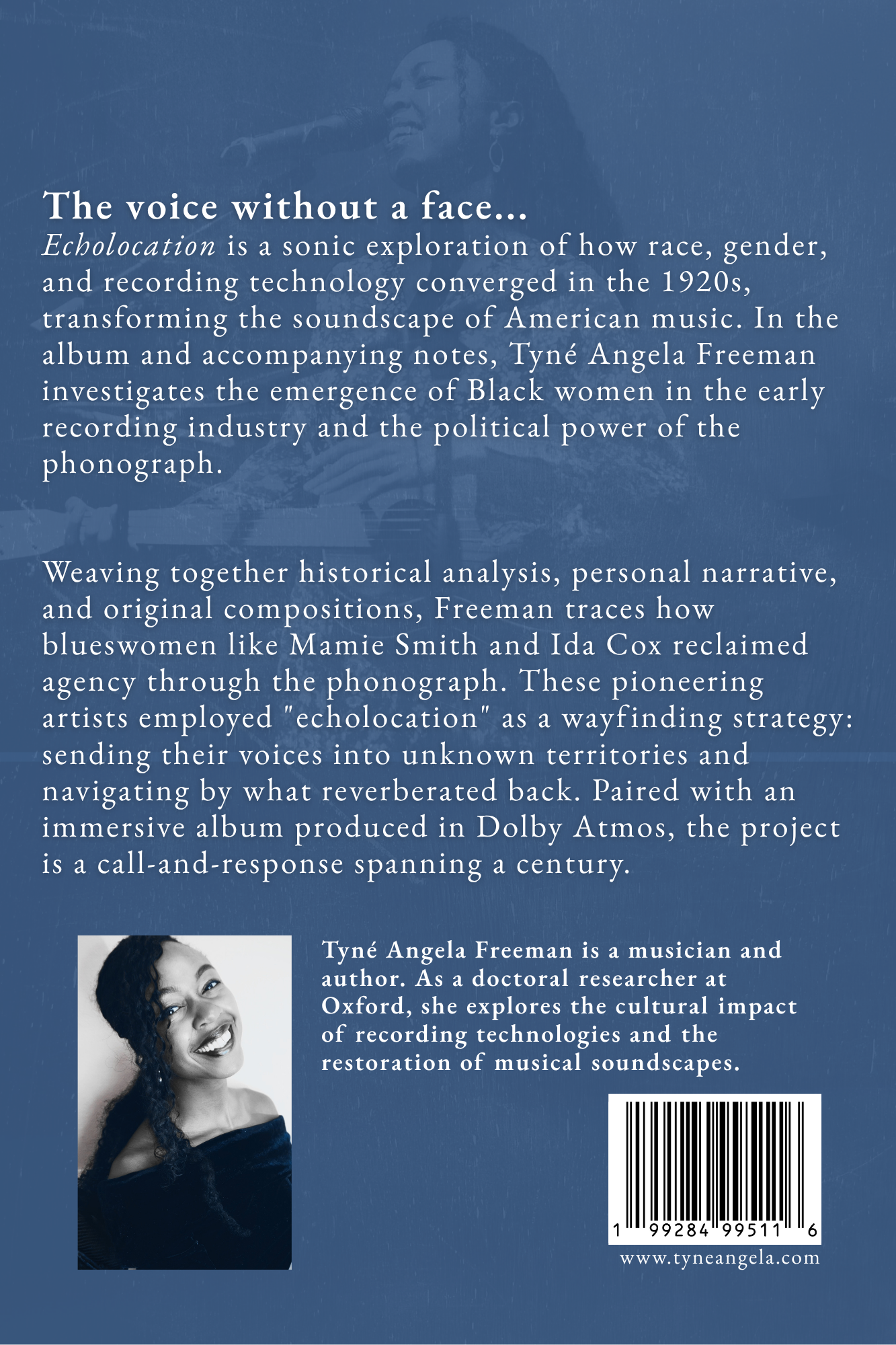

Echolocation is a sonic exploration of how race, gender, and recording technology converged in the 1920s, leading to the emergence of Black female blues singers. I position the phonograph as a revolutionary technology that transformed Black women from exploited and accessible bodies with silenced voices into amplified voices emitted from inaccessible, remote bodies. The project traces how blueswomen like Mamie Smith and Ida Cox reclaimed agency through the phonograph. These pioneering artists employed "echolocation" as a wayfinding strategy: sending their voices into unknown territories and navigating by what reverberated back. Paired with an immersive album produced in Dolby Atmos, the project is a call-and-response spanning a century.

ECHOLOCATION: The Ghosts in the Groove and the Blueswomen Who Made Them Sing

INTRODUCTION

The phonograph changed everything. With its whirling discs and voices etched in grooves, it collapsed the space between singer and listener. As the early twentieth century spun into motion, Black Americans fled the terrors of the South, seeking new lives in northern cities. Women of all races fought for the right to vote. Black thought leaders championed a 'New Negro' identity, rejecting centuries of degradation and demanding self-determination. Black women stood at a unique crossroads, fighting for racial uplift, gender equality, and their right to be heard. The phonograph emerged in these turbulent decades as both witness and amplifier, undergoing rapid advances and gradually becoming a mainstream commodity.

Then, in 1920 Harlem, a seismic event: a 28-year-old vocalist named Mamie Smith stepped into a recording studio. Her blues songs, released by the small, independent OKeh Records, exploded onto the scene, defying all expectations. It was a commercial triumph and a cultural shockwave. The record shattered industry norms, prompting other labels to scramble for their own 'race records,' compositions marketed primarily to Black consumers. Suddenly, the raw, powerful voices of Black women singing blues, jazz, and gospel began to echo across the nation. For women who had historically faced a triple confluence of race, gender, and class oppressions, this was particularly significant.

My analysis of the phonograph's real and symbolic impact is this: the Black woman is transfigured from an exploited and accessible body with a silenced voice, to an amplified voice emitted from an inaccessible, remote body. The phonograph became a conduit, transforming vulnerable bodies into an amplified presence. It was a paradox and a profound shift: The voice without a face. It stirred anxiety in some and awe in others. But above all, it etched the sound of Black womanhood into the grooves of America's memory.

Throughout the 1920s, a series of groundbreaking recordings by Black women broke a centuries-long silence. Through the static crackle of shellac grooves, voices once confined to porches and pews now traveled by rail, radio, and record. These women did not just sing the blues. They sculpted them into a definitive genre, shaping sound into sanctuary, rebellion, and confession. Navigating the turbulence of cultural change and the darkness of centuries past, they sent their voices out into the unknown, locating themselves by what reverberated back. I call this echolocation. Their songs were maps, and their lyrics were legacy. Decades later, I find myself haunted in the best way by those who sang before me. This album is my response to that call.

The album was produced, mixed, and mastered in immersive audio. For a project rooted in echolocation, this sonic architecture felt inevitable. Like the blueswomen who sang into gramophones and radios, I am sending out a signal and listening to locate. Through the mechanism of echolocation, a being sends out a sound and listens for what returns. This is how bats navigate darkness and dolphins locate each other across vast depths. It's also how the blueswomen, denied space and stage, used sound to declare: I'm here. We're here.

Immersive audio expands sound beyond the fixed frame of left and right, creating space for memory, spirit, and story. It doesn't constrain the music, allowing sound to surround the listener. Voices hover, linger, and depart. Notes swirl above, behind, and around. You don't just hear the song; you're inside of it. And that's how I wanted this story to be told. Each note or breath is given dimension and direction. The album was mixed in Dolby Atmos, a spatial audio format that allows sounds to move freely in three dimensions. Each instrument, vocal harmony, and century-old sample was positioned with intention, to evoke motion, intimacy, and resonance. Immersive audio is often described in technical terms: channels, objects, spatial mix. But here, it becomes something else. A reckoning. A reclamation. It's a way to make room for the voices history tried to flatten. To give presence and projection to those long dismissed or disembodied. The blueswomen I studied didn't get to fill concert halls. But their records filled parlors and barrooms, church basements and kitchen radios. Now, a century later, their echoes surround us in spatial sound. In that way, immersive audio isn't just a format. It's a kind of justice.